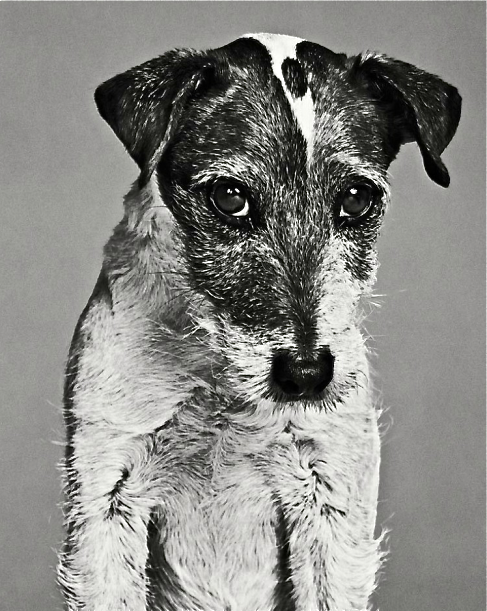

Dogs may empathize with humans more than any other animal, including humans themselves, several new studies suggest.

The latest research, published in the journal Animal Cognition, found that pet dogs may truly be man (or woman’s) best friend if a person is in distress. That distressed individual does not even have to be someone the dog knows.

“I think there is good reason to suspect dogs would be more sensitive to human emotion than other species,” co-author Deborah Custance told Discovery News. “We have domesticated dogs over a long period of time. We have selectively bred them to act as our companions.”

“Thus,” she added,” those dogs that responded sensitively to our emotional cues may have been the individuals that we would be more likely to keep as pets and breed from.”

Custance and colleague Jennifer Mayer, both from the Department of Psychology at the University of London Goldsmiths College, exposed 18 pet dogs — representing different ages and breeds — to four separate 20-second human encounters. The human participants included the dogs’ fur parents as well as strangers.

During one experimental condition, the people hummed in a weird way. For that one, the scientists were trying to see if unusual behaviour itself could trigger canine concern. The people also talked and pretended to cry.

The majority of the dogs comforted the person, parent or not, when that individual was pretending to cry. The dogs acted submissive as they nuzzled and licked the person, the canine version of “there, there.” Custance and Mayer say this behaviour is consistent with empathic concern and the offering of comfort.

As for what could be going on in the dog’s head, yet another recent study, published in PLoS ONE, showed how the brains of dogs react as the canines view humans. In this case, the researchers trained dogs to respond to hand signals that meant the pups would receive a hot dog treat. Another signal meant no such treat was coming.

The caudate region of the dogs’ brains, an area associated with rewards in humans, showed activation when the canines knew a tasty food treat was coming.

“These results indicate that dogs pay very close attention to human signals,” lead researcher Gregory Berns, director of the Emory Center for Neuropolicy, explained. “And these signals may have a direct line to the dog’s reward system.”

In that study, the reward was food, but Custance and Mayer think canines over the thousands of years of domestication have been rewarded so much for approaching distressed human companions that this may somehow be hardwired into today’s dogs.

The phenomenon in some cases could even have a subconscious element. Consider what happens when a person yawns and a dog is in the room.

“Dogs show contagious yawning to human yawns,” Matthew Campbell, an assistant professor in Georgia State University’s Department of Psychology, told Discovery News.

He said that “we have selected dogs to be in tune with us emotionally.”

Custance and Mayer next hope to determine how empathetic wolves may be.

“It would be interesting to see how wolves who have been raised in human households would respond if they took part in our experiment,” Custance said. “Would they behave like domestic dogs or show less response to a crying human? It would be fascinating to find out.”

Adapted from Discovery Channel